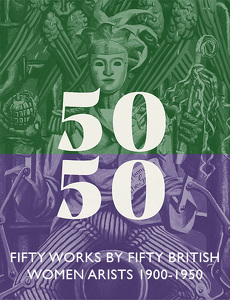

Nominated for the William MB Berger Prize for British Art History.

Ever since Linda Nochlin asked in 1971, ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’, art history has been probing the female gaze. Through scholarship and exhibitions, readings have been put in place to counter prevailing assumptions that artistic creativity is primarily a masculine affair. 50/50 functions as a corrective to the exclusion of women from the ‘master’ narratives of art. It introduces fifty artworks by known and lesser-known women – outstanding works that speak out.

Fifty commentaries by fifty different writers bring out each artwork’s unique story – sometimes from an objective art historical perspective and sometimes from an entirely personal point of view – thereby creating a rich and colourful diorama. This exhibition does not, however, attempt to present a survey or to address all the arguments around the history of women and art. Anthologies are of necessity incomplete, and many remarkable imaginations are not here represented.

Women artists have been set apart from male artists not only to their own disadvantage but also to the detriment of British art. While there were some improvements for women to access an artistic career in the twentieth century in terms of patronage, economics and critical attention – all the things that confer professional status – women had the least of everything. By showcasing just a few of the remarkable works produced, this exhibition draws attention to the fact that a vision of British twentieth century art closer to a 50/50 balance would not only provide a truer account, but also a more vivid and meaningful narrative.

Unsung Heroines

Unsung Heroines

![Evelyn-Dunbar: Studies-for-Various-Women’s-Land-Army-Activities,-Including-Singling-Turnips-[HMO-313]](/pix/6725.jpg)