Hover over the painting to magnify (there may be an initial delay while the magnified image is loaded)

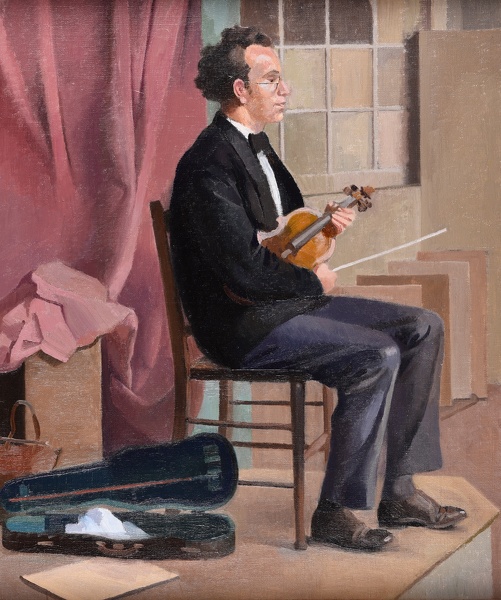

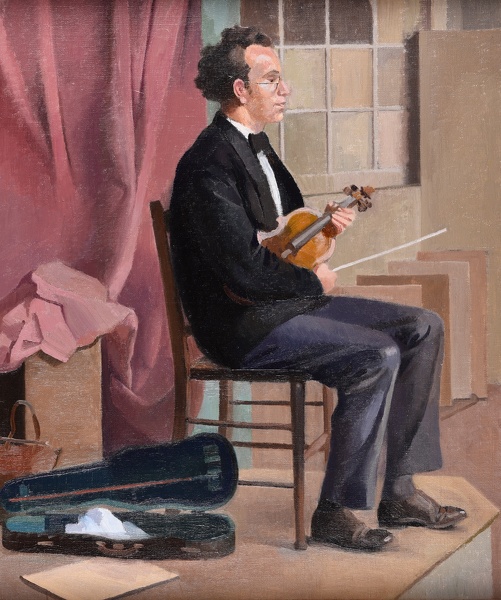

Hover over the painting to magnify (there may be an initial delay while the magnified image is loaded)Phoebe Willetts-Dickinson (1917-1978):

Portrait of a Jewish Refugee, circa 1939

Framed (ref: 7806)

Oil on canvas

See all works by Phoebe Willetts-Dickinson oil Portrait men war Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900 - 1950 World War II Paintings by British Artists

Provenance: The Artist's daughter; Private Collection

“There are no artists in Fascist countries”, declared Cyril Connolly in 1938. It is an outrageous comment, but shows how polarised the world was at the time Phoebe Willetts-Dickinson painted a Jewish refugee. Willetts- Dickinson was radically anti-war. Shortly after studying at the Royal Academy Schools she joined the Land Army, where she met and married the conscientious objector Alfred Willetts, 1942. Yet she wanted to draw attention to the plight of the German Jews. Her depiction is remarkably straight – compare it to John Craxton’s romanticised pen and ink drawing in the Tate, Dreamer in the Landscape (1942).

Antisemitism was not limited to Nazi Germany. It was rife in the whole Christian world. Willetts-Dickinson was religious; indeed, in 1966 she became the first Deaconess in the Church of England. As a feminist she campaigned for the ordination of women, but over and above this she was concerned with social justice, and she spent six months in jail for civil disobedience. Painting was ultimately not enough.

When Craxton drew his urbane Jewish friend Felix Braun as a shepherd in a landscape, he was sharing a house with Lucian Freud and Braun. Yet Craxton’s picture is only an oblique social criticism. Willetts- Dickinson’s picture shows an abandoned man. He is on the stage, but on the very edge of it. The plight of the Jews should have been on the world stage, but who was paying attention? This particular lonely man has unpacked his case; its contents, a violin and bow on his lap, and he waits patiently. He is in a desolate corner. The stage curtain that would be pulled back for any serious performance is still down except for a mouse-door of entrance. There is just about room for him to have crawled in, but what next?

Commentary by Alistair Hicks. Hicks is the author of Global Art Compass (2014) and is currently curating The Time Needs Changing at Pera Museum, Istanbul and The Crime of Mr Adolf Loos at Axel Vervoordt Gallery, Antwerp.

Unsung Heroines

Unsung Heroines SOLD

SOLD